Zero Hedge

Zero Hedge

Economy

The Euthanasia Of The Saver

by Eric Matias Tavares of Sinclair & Co., via Zero Hedge.com :

What have been the economic consequences of ultra-low interest rates? The answer might not be as hopeful as you may think.

While better known for the role of government in stimulating the economy, John Maynard Keynes, one of the most influential economists of the 20th century, also provided the intellectual framework for a big reduction in interest rates with two goals in mind: to reduce economic inequality and to achieve full employment.

Here’s what he had to say about the “rentier” (a quasi-Communist term for “saver”) in Chapter 24 of his seminal book “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money”, published in 1936. It requires some effort to go through it (and even more to comprehend it, if at all) but because it influences so much of the current economic thinking it is worth it [our emphasis in bold]:

“The outstanding faults of the economic society in which we live are its failure to provide for full employment and its arbitrary and inequitable distribution of wealth and incomes.

(…) Since the end of the nineteenth century significant progress towards the removal of very great disparities of wealth and income has been achieved through the instrument of direct taxation — income tax and surtax and death duties — especially in Great Britain. (…) For we have seen that, up to the point where full employment prevails, the growth of capital depends not at all on a low propensity to consume but is, on the contrary, held back by it; and only in conditions of full employment is a low propensity to consume conducive to the growth of capital.

(…) The justification for a moderately high rate of interest has been found hitherto in the necessity of providing a sufficient inducement to save. But we have shown that the extent of effective saving is necessarily determined by the scale of investment and that the scale of investment is promoted by a low rate of interest, provided that we do not attempt to stimulate it in this way beyond the point which corresponds to full employment. Thus it is to our best advantage to reduce the rate of interest to that point relatively to the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital at which there is full employment.

(…) I feel sure that the demand for capital is strictly limited in the sense that it would not be difficult to increase the stock of capital up to a point where its marginal efficiency had fallen to a very low figure. This would not mean that the use of capital instruments would cost almost nothing, but only that the return from them would have to cover little more than their exhaustion by wastage and obsolescence together with some margin to cover risk and the exercise of skill and judgment. In short, the aggregate return from durable goods in the course of their life would, as in the case of short-lived goods, just cover their labour costs of production plus an allowance for risk and the costs of skill and supervision.

Now, though this state of affairs would be quite compatible with some measure of individualism, yet it would mean the euthanasia of the rentier, and, consequently, the euthanasia of the cumulative oppressive power of the capitalist to exploit the scarcity-value of capital. Interest today rewards no genuine sacrifice, any more than does the rent of land. The owner of capital can obtain interest because capital is scarce, just as the owner of land can obtain rent because land is scarce. But whilst there may be intrinsic reasons for the scarcity of land, there are no intrinsic reasons for the scarcity of capital.

(…) I see, therefore, the rentier aspect of capitalism as a transitional phase which will disappear when it has done its work. And with the disappearance of its rentier aspect much else in it besides will suffer a sea-change. It will be, moreover, a great advantage of the order of events which I am advocating, that the euthanasia of the rentier, of the functionless investor, will be nothing sudden, merely a gradual but prolonged continuance of what we have seen recently in Great Britain, and will need no revolution.”

Indeed, no revolution was needed. Interest rates have generally declined over the last 30 years. However, the latest (last?) phase of this decline has been largely caused by unprecedented intervention from the world’s leading central banks in the form of ultra-low interest rates and successive rounds of quantitative easing, where trillions in primarily government securities have been purchased.

As a result, capital has been cheapened indeed. At this point there are almost €3 trillion worth of European bonds that have negative yields. If he were alive today, Keynes would no doubt be applauding all of this and giving high fives to his central bank followers.

Now, in the 1930s, with the Western world reeling from the effects of the Great Depression, perhaps it was understandable that a leading economist should became enamored with the virtues of central planning in lieu of the “cumulative oppressive power of the capitalist”, particularly when glancing over the propaganda of the Fascist and Communist regimes of those days and their impressive (and false) economic achievements.

But policymakers today, with the benefit of hindsight, should have known better. At the very least two lost decades in Japan should have been sobering enough.

Well, six years after the implementation of ultra-low interest rate policies on both sides of the Atlantic we should have enough data to figure out whether they are working or not.

And so far, neither of Keynes’ objectives has been achieved: employment growth since the 2008 crisis remains uncharacteristically sluggish, despite substantial gains in asset prices, and income inequality has surged to the point of concerning even Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen (actually, we were blown away by how similar what she had to sayabout this topic is to what Keynes described in the aforementioned Chapter 24).

So who is benefiting from these policies?

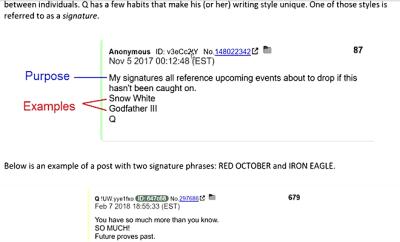

In November 2013 the McKinsey Global Institute published a very insightful discussion paper titled “QE and ultra-low interest rates: Distributional effects and risks.” It should be required reading for anyone with an interest on this topic. As a teaser, here are some of the graphs that highlight major income distribution consequences of central bank intervention since 2007.

Estimated cumulative change in net interest income (USD bn, converted at constant 2012 exchange rate): 2007–12

Source: McKinsey Global Institute.

According to McKinsey, governments and non-financial corporations have been the primary beneficiaries of ultra-low interest rates. Why? Because they are the largest net borrowers in the economy.

And borrowing they did, with government debt ratios rising sharply over the period; no good Keynesian would have used this extra cash to repair government finances. Not to be outdone, corporate managers also levered up, using the proceeds from debt issues to buy back their shares – lots of them, which has been one of the pillars of the big equity bull market we are in.

The impact on the banks varied greatly depending on geography: American banks have largely gained from low interest rates, British banks have suffered losses as a result and in the Eurozone they have been hugely detrimental to banks’ profitability.

The ones who have undoubtedly lost out were those quintessential Keynesian villains: the savers. These include pension funds and life insurance companies, households and foreign investors. The medicine prescribed by the central banks to correct their “bad” ways has cost them billions. And given that yields have continued to go down since McKinsey’s report was published, their misery has only increased. More high fives from Keynes!

And yet, even within those groups the impact has been uneven. Who in the household segment is suffering the most because of ultra-low interest rates? The retirees, of course.

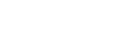

The following graph shows just how disproportionate this impact has been in the US:

Annual net interest impact for the average US household (USD bn, % 2007 income)

Source: McKinsey Global Institute.

And there you have it. It is the “baby boomers” who have suffered the most as the result of ultra-low interest rate policies. These folks worked hard all their lives, created the most prosperous generation the world has ever seen and now they are rewarded with virtually nothing on what they managed to save over the years. Try explaining to them that on top of that their central banker wants to prop up the inflation rate – in other words, what they pay for goods and services.

Keynes, as far as we can tell, did not explicitly factor demographics into his theory of employment. Depriving an ageing population of the income they earn on their accumulated savings will leave them with less funds available for consumption.

What is a retiree to do? Keep on working. According to the BLS, in the US the only group which has managed to increase its employment-to-population ratio is the 65 years or older, going from 20% in June 08 to 23% in March 15. In comparison, men aged 16-64 decreased from 81% to 77% and women aged 16-64 from 69% to 66% over the same period.

But the younger ones are not only facing greater competition for jobs from their elderly; they may also need to step in and take care of them at some point. Furthermore, their pension plans are not doing that great either. While the value of the assets which have been invested for their retirement has gone up, so has the discounted value of the bills they will have to pay (lower interest rates = higher present value).

Surely none of this can galvanize their “propensity to consume”, as claimed by Keynes. And neither will be paying for all those government debts to stimulate the economy.

So how do hardcore Keynesians react to all this evidence?

Like they always do: claiming the reason why such policies are failing is because they haven’t been as robust as they should be. We need more and with more vigor! Therefore, you are now hearing talk about even lower negative interest rates, taxation on deposits and banning cash transactions.

It seems like they don’t want you as a saver just euthanized; they want you buried as well.