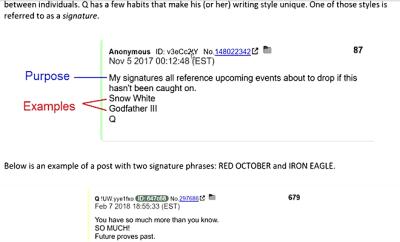

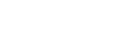

Spiegel.de/AFP

Spiegel.de/AFP

Featured

Kidnapped in Mozambique: In the Clutches of Rhino Poachers

By Bartholomäus Grill, via Spiegel.de:

We traveled to Mozambique to report a story about the region’s destructive and illegal trade in rhinoceros horns. But when photographer Toby Selander and I were taken captive by poachers, we found ourselves staring death in the face.

Just a short time ago, I was taken hostage in a small Mozambique village. Now I’m speeding through the bush in a pick-up truck driven by the boss of a criminal gang, his underlings hooting and hollering in the back. They are going to “finish” me, they had told me earlier, and I am convinced that they will stop at the next clearing and beat me to death like a dog. For the first time in my almost 30 years as a correspondent in Africa, I am afraid for my life.

I had arrived in Mozambique with Swedish photographer Toby Selander a few days earlier to report on rhinoceros poaching and the illegal rhinoceros-horn trade. We were hoping to follow the supply chain from the slaughter of the rhinos in South Africa through middlemen in Mozambique to the horns’ ultimate buyers in Vietnam.

The South African savannah is home to 21,000 of the world’s remaining 28,500 rhinoceroses. In 2014, some 1,215 of the animals were shot dead by poachers in South Africa alone, their horns sawed off for profit. That means that every seven hours, there is one less rhinoceros in the world. The animals have been around for millions of years, but if poaching continues at its current pace, environmentalists fear that they could soon become extinct.

“We are fighting for the conservation of a species,” says a wildlife ranger in Kruger National Park, the world-famous game reserve in northeastern South Africa that is home to the largest population of rhinoceroses in the world. “We are at war.”

From Africa to Vietnam

For the last several years, South African security personnel have been fighting a defensive battle against the rhino hunters. Anti-Poaching Units have been formed and are occasionally augmented by police and military troops. They use drones to scan the park’s vast, complex terrain — searching for the 15 poaching teams that, according to estimates by park management, hunt there on an average day.

Eighty percent of the poachers come from Mozambique, most of them from the underdeveloped border region across the Olifants River. The illegal hunts represent the region’s most important source of revenue and they guarantee an enormous profit margin: On the black market, one kilo of rhino horn goes for up to $80,000. The stuff is more valuable that gold or heroin, and the two horns of an average-sized rhino weigh almost six kilograms.

The exploding demand for rhinoceros horn in the Far East, particularly in Vietnam, has driven up prices. In recent years, Vietnam’s rapid economic growth has produced a broad middle class that can suddenly afford exotic animal products, like ivory, bear gall bladder and tiger-bone powder. By purchasing these products, people demonstrate their upward social mobility.

Rhino-horn powder is in particularly high demand. It is viewed as a miracle drug that can reduce fever, alleviate pain, stop nosebleeds and cure serious illnesses, including cancer. These beliefs are nothing more than absurd superstition — rhinoceros horn, like human fingernails or hair, consists primarily of keratin and has no medicinal qualities whatsoever. But many Vietnamese continue to believe in the 2000-year-old myths about the horns — which helps explain why there are no Javan rhinoceroses left in the country. The carcass of the last remaining animal was found in 2010 in the Cát Tiên National Park. Since then, animals in Africa have been forced to supply the growing demand.

The primary trade route leads directly through Mozambique and more horns change hands in the area surrounding Massingir than anywhere else. The dusty town on the South African border is the “capital” of the so-called kingpins, the poaching bosses. Twenty of them are thought to live here and their houses are unmistakable: ostentatious villas rising up out of the bush between shacks and adobe houses with tiled exterior walls and tinted windows covered with metal bars. A life-sized plaster statue of Jesus stands on the balcony of one of the mansions.

‘You’ll Get Rich, but You’ll Die Young’

The residents of Massingir and the surrounding villages are poor farmers: They herd cattle, cultivate small fields and fish in the rivers. Their settlements have no electricity, no schools and no healthcare clinics, and most of the young men are unemployed. For a long time now, the easiest way to quickly make a bit of cash has been to poach. “You’ll get rich, but you’ll die young,” says one of the men. He doesn’t want to reveal his name out of fear of the rhino mafia.

When he needs a new job, the man says, he just goes to Carogé, a bar on the main road through Massingir. Local politicians, police officers, rangers and informants meet there under the shade of marula trees. We are told that this is where poaching-gang leaders recruit new “associates.” We ask about Navara, the most notorious of the lot, but everyone acts as though they had never heard the name.

The administration of Mozambique’s Limpopo National Park, just across the border from Kruger, is very familiar with Navara, whose real name is Simon Ernesto Valoi. He lives in the second village inside the reservation, a park employee says — Mavodze, just 15 kilometers (nine miles) away. The park official says he has met Navara a few times and that it is not difficult to find him. “Just drive over.”

So we just drive over.

The Limpopo National Park is a paradise for wildlife: wide-open wilderness crisscrossed by small streams, velvet-green hills, thick bush and umbrella thorn acacias. Soon, the reservation is to be linked up with other parks in Mozambique, Zimbabwe and South Africa to form the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park. It would be the largest nature reserve in the world and a place where big game could move freely across some 100,000 square kilometers (36,600 square miles), an area larger than Portugal.

A Dangerous Mistake

Navara’s house is easy to find: It is painted in bright colors and is the flashiest structure in Mavodze. We park on the dirt road in front of the fenced-in property and ask a woman on the other side of the fence about his whereabouts. Her husband, she says, isn’t home at the moment and she calls him on her mobile phone. Navara is furious.

Later, we’ll realize what we did wrong. We disregarded a crucial rule by not first going to the village elder. Such a procedure is normal in many parts of Africa, and those who ignore the local authorities harm the dignity of the entire community.

Minutes later we are surrounded by 50 or 60 people, apparently mobilized by Navara. Young men threaten us with their fists and curse at us: “Spies! Secret police from South Africa!”

“What do you want here?” an old man screams. “Navara is one of us. He gives us work.” People in Mavodze do not see poaching as being reproachful and most of them are only familiar with rhinoceroses because they are printed on the 20 meticais banknote. Navara, on the other hand, offers lucrative work to unemployed young men. The villagers are afraid of the poaching boss, but they also venerate him.

He is believed to employ 10 to 15 hunting teams, each consisting of three men. On bright, moonlit nights, they cross the border into South Africa with one person carrying a rifle or the tranquilizer gun and the second an axe to chop off the rhino’s horn. The third person is charged with hauling provisions. It is dangerous work. Between 2008 and 2014, 363 poachers were killed by South African security forces.

The “Hawks,” a special South African police unit believes that the raiding parties are only a small part of a much broader network that includes corrupt rangers, park officials, police officers, professional hunters and bush pilots. Game wardens are bribed to monitor the movements of the rhinoceros herds while veterinarians supply M99, an anesthetic. Local politicians, safari organizers, cattle traders and white farmers act as go-betweens.

The gang leaders are one rung further up the ladder. They sell the horns to smuggling rings that then bribe shipping companies, customs inspectors, port officials and airport personnel. Ministry employees and diplomats are often part of the criminal network. Indeed, workers at the Vietnamese Embassy ensure that the product makes its way to wholesalers in their homeland. South Africa has repeatedly launched investigations into suspect diplomats.

And there is apparently another route for getting the rhino horns to Vietnam: For the past several years, the Vietnam-Mozambique joint venture Movitel has been installing mobile phone masts and fiber-optic cables in the Mozambique hinterland. Some of their technicians are suspected of being couriers in the rhinoceros horn trade.

‘I Hate You Whites’

Back in Mavodze, one of the gang leaders has arrived: Justice Ngovene, aka “Nyimpini”, a brawny man wearing a black leather overcoat and a floppy hat. He accuses us of entering the village without permission. The men surrounding us are preparing to attack when a white Toyota Land Cruiser speeds up. The crowd cheers.

The license plate reads “Katana 2,” katana being the Japanese word for a large knife or long sword. The vehicle belongs to Navara, and he climbs out, a medium-sized, unremarkable man in his mid-30s with a shaved head and a gold chain hanging around his neck. He is accompanied by a half-dozen bodyguards. Navara has a reputation for being extremely violent and he orders us to go to the police station where he wants to press charges for trespassing.

We are interrogated in a small, windowless room. Where are you from? Who sent you? The two gang leaders — Navara and Ngovene — ask the questions while the village policeman only occasionally interjects. The bodyguards threaten to rape us, to kill us and to burn our corpses. The village policeman takes notes, his hands trembling.

Navara is sitting right next to me. He stares at me and hisses: “I hate you whites!” The expression on his face is fearsome, a look I will never forget.

Marilise Meyer, 37, will presumably never forget it either. On Feb. 3, 2009 not far from the South African village of Gravelotte, she was forced to watch as Navara stole her family’s car and cold-bloodily gunned down her husband when he tried to resist. Meyer later identified Navara from mug shots.

At the time, he specialized in car-jacking off-road vehicles — his favorites were Nissan Navaras, which is where his nom de guerre comes from. In South Africa, he has been wanted by the authorities for years for a double murder. “Why is this dangerous criminal allowed to still walk around freely?” wonders Marilise Meyer.

‘I’m in Command!’

A security consultant, whose company has collected information about Navara in the Massingir area for one of his clients, claims that it’s “because Navara is protected at the highest levels of government and by police leaders.” He says, “They prevent the extradition being sought by South Africa.”

The interrogation in Mavodze takes two-and-a-half hours before the decision is made to take us to police headquarters in Massingir. There, we are to be locked away. They want to separate the two of us and when we protest to the village policeman, Navara growls: “I’m in command here!”

In addition to police officers, Navara is also thought to “employ” local justice officials as well as political functionaries from the ruling Party, Frelimo. Former fighters from Renamo, an erstwhile rebel movement, allegedly work together with him as well. The group still has large supplies of weapons left over from the civil war with Frelimo and it finances itself with poaching, among other sources of revenue.

The man is apparently able to buy everything and everyone. One witness watched as Navara once walked into the local branch of Banco Comercial carrying bulging shopping bags filled with US banknotes. Rhino dollars.

Outside, in front of the police station, the mob is becoming increasingly aggressive. Their anger has another source as well. The government is planning to resettle everyone currently living inside Limpopo National Park, a total of around 9,000 people. The neighboring village of Macavene has already been cleared, and now it is Mavodze’s turn.

But the residents are resisting the move, not wanting to give up their homes, fields, cattle pens and watering holes. They want to remain close to the graves of their ancestors. Mavodze has been their home as far back as their collective memory reaches and now they are being forced to make way for a gigantic nature project which, from their perspective, only benefits wealthy safari tourists. White foreigners like us.

The angry young men in front of the station have decided to lynch us. Following the interrogation, gang leader Ngovene goes out onto the police station veranda to calm them down — and suddenly goes from being our tormentor to being our protector. His brief speech saves our lives — for the time being.

Seized by Fear

I’m forced to ride in Ngovene’s four-by-four while the photographer, Toby Selander, is put in a different car. They’re separating us — not a good sign. As I climb in, a boy gestures that he will cut my throat. He looks about as old as my own son, who is 15. We race towards Massingir in a column led by Navara’s four-by-four, and when Ngovene suddenly turns onto a rugged path in the bush, I’m seized by fear.

It turns out that he’s only taking a shortcut — and is slightly tipsy from drink. I try to engage him in conversation and he says that the rhino trade is a damn risky business and that he’s thinking about getting out of it. “Our area is on the upswing, so there are new opportunities there,” he says.

Massingir District’s economic potential is in fact enormous. The ground is fertile and thanks to the Massingir Reservoir, there’s lots of water. The government, together with an international consortium, is planning a 37,000 hectare plantation that will produce sugar and biofuel, and create 7,000 jobs. The new Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park is projected to attract millions of visitors from around the world and its establishment is being supported by foreign development organizations with the German Reconstruction Credit Institute (Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau) as one of its most important financial backers.

“If people had an alternative, maybe poaching would also decrease,” Ngovene says. He himself is planning to build a guest house for tourists — two stories, with 26 rooms, and a swimming pool on the roof. The shell has already been built.

“Do you know any investors from Germany who might be willing to join?” he asks. It’s a grotesque situation: Here I am completely under his control and he sees me as a potential business partner.

We finally reach Massingir police headquarters and the second interrogation begins. The gang-leaders and their thugs are once again standing in the room. They point to the inscription above the gated door: “Celas.” Cells. One of them threatens that we’ll be thrown in there, alongside imprisoned murderers. “And during the night we will sort you out.” For Navara, it wouldn’t be a problem. Everybody in Massingir knows that he works with the police. He supposedly even arms his teams of poachers by “leasing” confiscated assault rifles from the local police station.

The station chief, a man named Cambaco, berates us as outlaws and is openly on Navara’s side. His behavior only changes when his cell phone rings. The caller is his senior-most supervisor, the national head of police, who has been alerted to our situation by the German Embassy in Maputo.

Sleepless Night

After eight hours, we’re finally released. Night has fallen and Navara, Ngovene and their bodyguards are conferring. We’re afraid they may ambush us on our way to our remote accommodations. Cambaco, the police chief, assigns two officers with Kalashnikovs to protect us, for a “special fee” of $250.

During the sleepless night in our lodge, we feel trapped, as though we’re in a lawless space, subject to the capriciousness of criminal gangs.

Officially, Mozambique has been a parliamentary democracy since 1994. But in areas like Massingir, rule of law has yet to arrive. Here, police officers and public prosecutors are to be feared just as much as gang leaders. It’s an open secret that powerful politicians make money from the deals and, in exchange, protect the gangs from criminal prosecution. Regime critics who reveal official corruption are eliminated if necessary. Earlier in the week, Gilles Cistac, a respected constitutional expert who supports ideas of the opposition, was murdered in the middle of Maputo in bright daylight.

The next morning, we’re warned: The only access road to Massingir is controlled by Navara and his men. By now our lawyer from Xai-Xai, the provincial capital, has arrived and tells us we have no alternative but to appear before the court in Massingir. There, a prosecutor tells us that we are under investigation and that we are not allowed to leave Mozambique for another five days. There might even be a trial. In Massingir.

The district’s chief of police nevertheless advises us to leave the city as quickly as possible. An escort is quickly assembled to accompany us for the first 200 kilometers.

After two-and-a-half hours of driving, we are back in secure territory. In Macia, a place where we can no longer directly be threatened by the poachers, a delegate from the Swedish Embassy receives us.

It will take several more days before we are allowed to leave the country. Only after a prosecutor in Maputo assures us that trespassing charges have not yet been filed are we allowed to fly back to Cape Town.