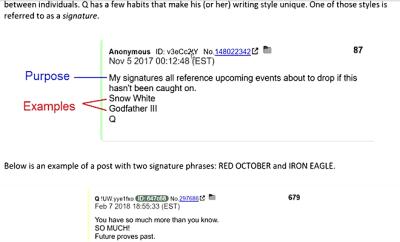

Donetsk city skyline (Roger Annis)

Donetsk city skyline (Roger Annis)

WW3

Bearing witness in Donetsk: Ukraine’s Euromaidan ‘revolution’ and the war in Donbas

by Halyna Mokrushyna, New Cold War:

For five days beginning April 13, 2015, I joined a media tour to the Donetsk region, the breakaway region of eastern Ukraine, which in 2014 said “no” to the Western-supported Euromaidan revolution in Kiev and western Ukraine.

This “revolution” started with a small group of students protesting against the last-minute decision in November 2013 of then-President of Ukraine Victor Yanukovych to postpone the signing of a proposed Ukraine-European Union Association Agreement.

According to many economists in Ukraine, as well as internationally, this agreement would seriously alter and damage Ukraine’s existing, close economic ties with the Russian economy. It would transform Ukraine from a country with developed heavy industry, technology and agriculture into a supplier of raw materials and cheap, educated labor to Western European markets. The European Union would gain a new, large market for European agricultural and other products along its eastern border. [1]

The agreement would not allow Ukraine to become a full-fledged member of the European Union, but for millions of Ukrainians, it was an important step toward integration into “European civilization” with its material well-being and democratic institutions.

Since independence in 1991, Ukrainian leaders have told the population that Ukraine was embarking upon a long road to join the family of the “civilized” European nations. Ukrainians have lived with this European dream ever since. So when President Yanukovych suddenly decided to postpone signing the agreement with the EU, without explaining to the population that the Ukrainian government needed more time to negotiate with Europe and Russia a smooth transition from a Russian-oriented to a European-oriented economy, pro-European Ukrainians rebelled. [2]

This rebellion was also a protest against a corrupt, oligarchic regime (ironically, not a lot different from all of the elected regimes since Ukrainian independence in 1991). The rebellion was supported by the opposition parties, which had previously tried unsuccessfully to mobilize the population in an all-nation action against Yanukovych. For all of his many faults, however, Yanukovych was elected in 2010 in a democratic and free election, recognized as such by the West.

A “European” future for Ukraine

The heart of the pro-European rebellion became the central square in Kiev, called Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square). Beginning in late November 2013, tents and field kitchens were installed to feed the people who came to be permanently installed on the square (two to three thousand on weekdays and ten thousand or many tens of thousands during the weekends).

On a central stage, singers, folk groups and rock bands would perform in succession, entertaining the crowds. Political opposition leaders, heads of civil society organizations, church leaders and ordinary citizens would take to the stage to speak of a “European” future for Ukraine and the necessity to fight corruption and eliminate the greedy oligarchs from power.

In this sense, Euromaidan really was a popular uprising in which Ukrainians self-organized and proved that they are active citizens shedding the skin of passive, docile “Soviets.” They were ready to take charge of their destiny and their country.

According to the Western press, Ukrainians were passing an exam on becoming a civil society through their Euromaidan “Revolution of Dignity.” The same press turned a blind eye to the dark side of this revolution: the extreme-right, ultra-nationalist paramilitary groups that radicalized the originally peaceful protests and turned them into armed clashes with the forces of order.

The right-wing groups transformed the pro-European and anti-oligarchic rhetoric of Euromaidan into ultra-nationalist, anti-Russian slogans such as, “Ukrayina ponad use” (Ukraine above all); “Smert voroham” (Death to enemies); and “Moskaliv na nozhi” (Moscovites to the knife).

They led assaults and the taking of administrative buildings in the center of Kiev. They threw Molotov cocktails at police and burned tires, covering the streets in dirty smog. They marched throughout Kiev with torches and portraits of Stepan Bandera, the World War II-era leader of the extreme-right, nationalist political and military movement in western Ukraine that collaborated with the Nazi German occupiers.

Southeastern Ukraine in its majority rejected this anti-Russian, Euromaidan revolution. They could hardly do otherwise. The majority of people there call Russian their mother tongue. They have profound ties to Russia. They consistently favor closer economic ties with Russia and the fledgling Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). [3]

Ukraine has always had this historical division between regions. Western Ukraine has been politically and culturally inclined toward Europe, while Eastern Ukraine has very strong economic and cultural ties with Russia. The Euromaidan revolution was an uprising of western Ukrainians. Over 50 percent of them took direct part in protests or provided assistance to the protesters, while about 47 percent did not participate at all. In the south and east of Ukraine, including in Donbas, the percentage of nonparticipation in Euromaidan exceeds 90 percent.

In southern Ukraine, roughly one-third of the population considers the Euromaidan “revolution” to be a coup d’état orchestrated by the opposition (19.4 percent) or by the West (14.2 percent). In eastern Ukraine, opinion is stronger: 24.4 percent say the Ukrainian political opposition was primarily responsible for a “coup” while 15.4 percent say it was the work of Western governments, for a total of almost 40 percent. In Donbas, a clear majority of the population (72 percent) believes that Euromaidan was a coup d’état: 51 percent consider that the West helped organize it and 21 percent believe that the political opposition did it.

Donbas strongly rejected Euromaidan. After the seizure of power in Kiev by the opposition on February 21, massive pro-Russian rallies erupted in major cities in southeastern Ukraine – Kharkiv, Odessa, Dnipropetrovsk, Luhansk and Donetsk. This was the beginning of the movement called the “Russian Spring” by its participants, inspired as they were by the Arab Spring of 2011.

In several towns and cities of southeastern Ukraine, including Kharkiv and Mariupol, pro-Russian protesters occupied buildings of regional administrations and raised flags of the Russian Federation. In Donetsk, protesters elected a “people’s governor” – the commander of the “People’s resistance of Donbas,” Pavel Gubarev.

What were protesters demanding? For them, the Kiev regime was illegal and illegitimate because it refused to hear the Southeast. On February 23, just a few days in power, the Kiev regime tried to abolish the 2012 language law, which accorded legal status to Russian as well as to other “minority” or regional languages in regions where native speakers of the language constitute 10 percent or more of the local population. [4]

Kiev also refused to hold a referendum in response to popular demands for decentralization/federalization of Ukraine’s administrative system. [5] Donbas had no say in deciding its future.

Donbas referendum and the “People’s Governor”

The Donetsk city council ceded under pressure from pro-Russian protesters and on March 1, at an extraordinary session, deputies decided to support the demands of protesters and to recommend to the regional council that it immediately hold a referendum on the future of Donbas. The city council decided to declare Russian a second official language in Donbas and to demand that the Donetsk regional council adhere to these decisions.

The city council also declared Russia as Donbas’ strategic partner. It decreed the creation of a municipal police force in order “to ensure the safety of citizens on the territory of Donetsk and the protection against possible aggression of radical nationalist forces”. The local authorities were to assume full responsibility for the functioning of the state institutions until such time as the legitimacy of the new laws adopted by the Verkhovna Rada (Parliament) in Kiev was established and the new authorities were recognized.

On Sunday, March 2, protests in Donetsk continued, with some 4,000 people on Oktyabrskaya Square in front of the Donetsk Regional Administration building, under the flags of Russia, the Soviet Union and several political organizations, including the Russian Bloc. People protested against the local and central powers and against a possible invasion of the region by the “fascists” from Kiev.

Protests continued the following day. Inside the regional administration building, the regional council was holding a session and representatives of the protesters entered the building with the assistance of police who cleared a corridor for them through the crowd. The representatives spoke to the regional council, asking it to declare the new Kiev government illegal.

People on the square started collecting signatures on a petition to hold a referendum regarding the statute of Donbas. After the regional council refused to recognize Pavel Gubarev, the “people’s governor,” as governor of the Donetsk region, protesters stormed into the building and some of them remained there, occupying two floors.

Birth of the Donetsk People’s Republic

On March 5, the Donetsk police managed to expel the protesters from the building under the pretext that a bomb was planted somewhere in the building. The same day, in the afternoon, protesters gathered in front of the building again and retook it. During the night of March 5 to 6, special forces of the Ministry of the Interior of Ukraine cleared the building of protesters, arresting around 50 of them.

Protests continued throughout March. On April 6, protesters occupied the administration building again. They declared an independent Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) and adopted an address to the Russian Federation asking it to formally accept the Donbas region into its fold. A date for a referendum on the future of the DPR was set for May 11.

On April 10, the DPR started to form its own military units, a so-called people’s army. On April 13, representatives of the newly created DPR, supported on several occasions by locals and the police, took under their control administrative buildings in several cities across the region. They installed checkpoints on several roads.

On April 14, Kiev launched its fateful “Anti-Terrorist Operation” against the rebel movement in the east, calling the rebels in Donetsk and Luhansk “Russian separatists” and “terrorists”.

On April 18, the insurgents raised the flag of the DPR at the Donetsk airport. On April 27, the Donetsk regional state television station was taken under DPR control.

On May 11, a referendum was held throughout the Donetsk region in which one question was asked in two languages, Ukrainian and Russian: “Do you support the act of the state independence of the People’s Republic of Donetsk? Yes or no?” According to the election commission of the DPR, 74.87 percent of people voted. The vote result was as follows: 89.07 percent were for the independence of the DPR while 10.19 percent were against. The DPR had de facto come into existence.

Bearing witness in Donetsk

I present this lengthy description of the history of the past year as background of my trip to Donetsk in April of this year and the motives that have pushed me to speak up against the current political regime in Kiev. The governing regime in Kiev is trying to build a monolithic, ethnic Ukrainian state and culture which excludes the multiethnic, Russian-speaking Donbas. Kiev prefers fighting and killing instead of negotiating.

In the articles to follow in this series, I will write about what I saw and witnessed in the city of Donetsk and the Donetsk region: people who are struggling to build a new political and social order, based on social justice and socialist principles, free of corruption and oligarchs; elderly women and men, young mothers and their children, victims of the armed conflict in Donbas, who are stuck in ruined houses and basements, enduring constant shelling, with nowhere to go; a young woman who joined the armed resistance of the Donetsk insurgency; a veteran of the special police force of Ukraine (the Berkut) who witnessed the destruction of the Ukrainian state on Maidan Square and, after returning home to Donetsk, became one of the leaders of the Anti-Maidan movement in the region; an orthodox monk, abbot of a monastery, who wants Ukraine and Donbas to live in peace; tears of an elderly Ukrainian woman from western Ukraine who had moved to Donetsk several decades ago and told me that there was never a Ukraine in Donetsk; a former owner of a wedding agency who became a member of Novorossiya parliament; an engineer from Zaporizhia who was a participant in the Russian Spring and had to flee his home city, fearing for his life and that of his family.

All of these stories affected me as a human being, as a researcher and as a Ukrainian. I will relate these stories to you as fully and objectively as I can. I hope that through them, we will understand better the drama that is taking place in Donbas. I also hope, no matter how illusory this hope is, that Ukrainians and the international community will hear the people of Donbas and instead of labeling them terrorists and separatists, will accommodate their legitimate demand to live on their land, speak the language of their choice and celebrate as they see fit the victory of their grandfathers and great-grandfathers over Nazism in World War II.

This article originally appeared at Truthout.org on June 2, 2014. All of Halyna Mokrushyna’s writings from Donetsk and on Ukraine more generally can be found on her dedicated article page at The New Cold War: Ukraine and Beyond.

Notes:

[1] The population of Ukraine is about 45 million people. It is the third-biggest country in Europe in territory – 603,700 square kilometers, after Russia and France. Ukraine’s most important exportsprior to 2012, when Euromaidan took place, were military equipment, metals, pipes, machinery, petroleum products and agricultural products. Ukraine, with its fertile grounds and rich black soil, is among the first 10 world producers of wheat and corn, the world’s largest producer of sunflower oil and a major world-scale producer of grain and sugar.[2] I remember reading somewhere on the internet an apt comparison of this situation with an abrupt stop of a train or a bus and passengers, having not had the time to hold onto something, are propelled forward by inertia and pile one on another at the front of the bus.[3] See, for instance, an April 2014 survey, conducted by Kiev International Institute of Sociology. In this survey, 47.7 percent of residents of southeastern Ukraine would join the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), compared to 24.7 percent who favored joining the European Union.[4] The description of the Russian language in Ukraine as a “minority” language as done in the 2012 language law is very problematic, if not downright wrong. But it is beyond the scope of this article to analyze this.[5] Yanukovych was no wiser. On February 14, when the fire of Euromaidan was in full swing in Kiev and violence was escalating, he was explaining to journalist Vitaly Korotich that federalization was not on the agenda because this question had to be studied carefully and not decided “on emotions.” Yanukovych said, “Our priority is to preserve our state. This should be our main concern.”

Read also:

Families describe fleeing war-torn Ukraine for Russian camps, by Halyna Mokrushyna,published in Truthout.org and New Cold War.org, May 24, 2015